Watch as Jeremy, JP and Peter Drew rush to repair Hurricane Fiona damage on Green Island before the Cahows return in late October for the start of the 2022/23 nesting season.

Cahow Colony damage assessment after passage of Hurricane Fiona

The team conducts a damage assessment after the passage of Hurricanes Fiona & Earl

Hurricane Fiona LiveStream

Hurricane Fiona @ 11 pm September 22nd

Watch the LiveStream from the Surface Cam on Nonsuch Island and tune in around sunrise when daylight should show the effects of Hurricane Fiona during its closest approach with 90knot winds and 30 ft to 45 ft seas on top of a 3 ft storm surge and a high-tide at 7:35 am. This will be a horrendous combination for all of the exposed South Shore, especially the West end but also extending as far as Nonsuch… Hopefully, the solar power array and new wireless internet from Horizon (huge thanks!!!) holds up so that we can keep watching.

Thankfully the Cahows are out at sea this time if year, and not due back until November… Stay tuned for a post storm assessment of the coastal erosion that we are undoubtedly experiencing.

Below is a replay of the LiveStream recorded at 9am during the closest approach.

Hurricane Earl Nonsuch Beach Erosion

When Hurricane Earl’s eye passed 80 miles to the east of Bermuda on September 9th, we were spared from major wind damage however we were still impacted by the resulting high seas.

Though it ended up being not as bad as expected, Nonsuch’s South beach was still eroded. Watch the video below for Jeremy’s description.

Anticipating that this might happen the Nonsuch Expeditions and DENR teams preemptively removed a 5-month collection of Ocean Plastics that was being stored temporarily on the side of the dunes. It was being amassed there during the beach cleans being conducted every time the team visit the island as part of an ongoing project being sponsored by Axis.

Stay tuned for the next update after our Hurricane Fiona assessment.

Watch Nonsuch Island LiveStream for expected 25 ft swells from Hurricane Earl

Radar image of Hurricane Earl at 3 am September 9th

The Nonsuch Expeditions and DENR teams have been busy the past few days preparing for the passage of Hurricane Earl. Whilst we are fortunately not expecting a direct hit with hurricane Earl currently projected to track 100 miles to our south/east, we are still expecting 18ft to 25ft ocean swells which will impact Bermuda’s South shore including the ocean-facing side of Nonsuch Island.

Fortunately, the Cahow nesting season does not start until November so they are not currently in their burrows, as several of the outlying islands and rocks where they nest will be submerged by the expected 18ft to 25ft ocean swells.

Over the past few days Jeremy, assisted by JP rescued two Longtail chicks which were in low lying nests that were sure to be submerged by the expected ocean swells, see video:

On September 7th Jeremy, JP and Peter Drew relocated over a ton of ocean plastics that was being stored for further study in the dunes above the beach, which would have undoubtedly been swept back out to sea if left in place. Video to follow.

UPDATE Sept 9th 9am After the passage of Earl overnight the seas have mostly settled. Jeremy and JP will be conducting a survey of expected coastal erosion as soon as conditions allow, and will be post the results as soon as possible.

Watch the current LiveStream from our CahowCam Surface Cam from Nonsuch Colony A:

Totoro the CahowCam 2 chick has fledged!

UPDATE: June 4th @ 00:40 AM, “Totoro” the 2022 CahowCam 2 Bermuda Petrel Cahow chick has fledged!

We are processing the first flight replays etc., please check back shortly…

If you have enjoyed this season please consider supporting our efforts.

Here are her June 4th & 9th, last health check videos, the fledging highlights will be uploaded shortly.

Totoro the CahowCam 2 chick is about to Fledge!

As part of our record-breaking Cahow Nesting Season, tune in tonight to watch LIVE as "Totoro" the newly named CahowCam2 chick prepares to fledge!

Our Team will do their best to control the CahowCam3 Surface Cam to track her as she makes her way around the Colony imprinting and exercising throughout the night.

Unlike her neighbors, which tend to explore further, over the past few nights, she has been making very short trips just beyond her burrow entrance, never roaming very far before retreating to hide in the tunnel or back in the burrow to take a nap.

Yesterday when Jeremy conducted her latest health check her wing chord was 265 mm and her weight was 294 grams well within fledging parameters, so she could go at any time.

A good watching strategy can be first to check the CahowCam2 LiveStream to see if she is in the burrow, and if not she is either in the tunnel resting, or, and only when it is dark outside, she may be outside roaming around and hopefully still visible on CahowCam 3 if we still awake and able to remotely track her.

We will be also be posting updates to the Twitter feed found embedded further down on the CahowCam page:

Either way, stay tuned for a regular Newsletter with a full update and highlight replays.

Longtails (White-tailed Tropicbirds) nesting on Nonsuch Island

When longtails are sighted again near Bermuda's shores in February and March, locals know it is the beginning of Spring! Bermuda is critical to the life history of these seabirds, which nest in the crevices of our seaside limestone cliffs.

This fantastic footage was captured by Patrick Paley whilst on an Audubon Nonsuch Island tour. It shows an adult longtail stopping in mid air to have a closer look at the cliffs of the Nonsuch Island southwest point.

Longtails spend most of their time on the wing - their legs are set back too far on their bodies to walk on land, and instead bump along on their chests when they are confined to rocky crevices during nesting. Their single egg is generally laid in April and May, and hatches in June and July, however should this first egg fail, they have been known to head to sea for a month to recharge, and then return and try again resulting in late summer chicks.

Longtails are threatened by introduced species and habitat destruction - their cliff-front nesting sites are destroyed by coastal erosion, and dogs, cats, rats and even ants can threaten the vulnerable chicks. 'Longtail igloos', made of styrofoam and concrete, have been installed in many locations on mainland Bermuda and Nonsuch to give the birds more spots to nest.

Aside from being home to the Cahow Recovery Project, Nonsuch Island is also used as a site for the intensive management of longtails, in order to increase their breeding success including 63 igloo nests out of the 210 nests on the island. On our website, you will find a link to the TropicbirdCam, a sister project to our CahowCams, where you can watch the progress of our longtail chicks, from egg laying in March to fledging in September.

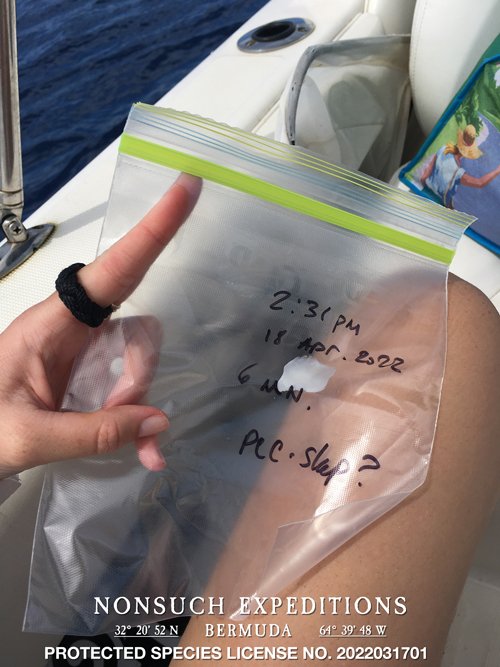

Collecting DNA from Whale Skin for the Sound of Science Project

Photo by Research Assistant Rosa Sirera-Aransay

When whales perform surface behaviours - like slapping their tail or pectoral fins, or jumping out of the water for a breach, lots of skin sloughs off their bodies into the water. In fact, one of the many theories for why whales breach is to remove parasites and exfoliate their skin.

“I never knew whales left so much material in the water before Nan explained it,” Jean-Pierre Rouja, project co-founder says. “ Alongside the whale songs the we are recording and archiving, the DNA that will be extracted from their skin is crucial for giving us more information on the whales that we identify in the Sound of Science project.” (Being conducted under PROTECTED SPECIES LICENSE NO. 2022031701)

These little flakes are sloughed-off skin from a humpback whale!

Sometimes the pieces of skin are so large, they can be seen floating in the water in a whale footprint – an area of smooth, glassy surface water left as a consequence of whale movement.

Nan Hauser, project co-founder says: “We can tell many things from whale skin … for instance the species, genetic clade, what they have been eating, their health, and much more. It is more common for us to find sloughed skin in the warmer waters than the colder waters. It is also more common to find sloughed skin from a female that has just given birth. We try hard to collect a piece of skin from every whale encountered but it is sometimes difficult.”

Nan has also collected whale placenta, bloodclots, cookie cutter shark bites of whale flesh, calf spew, whale poo, and sperm in the water. Do not make the mistake of going to Nan’s freezer to look for a midnight snack!

As soon as a whale breaches, the Sound of Science team enters the footprint it has left behind in order to scoop skin from the water with a net.

The Sound of Science project team can identify individual whales by photographing the ventral side of their tail flukes or the right and left side of their dorsal fins. Each whale fluke has different markings that can help with differentiating it from others in a group. The DNA analyses from the skin samples are matched to our ID photos, and to records of the whale’s observed behaviour.

Here, you can see research assistant Choy Aming using tweezers to carefully remove collected skin from the sampling net. The pieces are quite large as they were collected from a breaching whale. Choy avoids touching the skin with his fingers, as it can contaminate the sample. Tweezers are sterilized with ethanol between net scoops. The skin is placed into a sample bag, which is labelled with the species – always Megaptera novaeangliae for this project – number of whales present, latitude and longitude of where the sample was scooped from, the time and date it was collected (which together with voice logs, help connect it to photographed fluke ID’s) and if there was a behaviour associated with it.

On one of the Sound of Science research days, research assistant Eric Manfra scooped something bright white from the water,which is probably a piece of skin from a humpback’s long pectoral fin since it as slapping its fin on the surface of the water.

On the same cruise, research assistant Fae Sapsford scooped a whale louse that was floating in the water after a breach.

Whale lice are little parasites that usually live on the skin of whales, settling in any crevice on the whale’s body that will protect them from water currents - like near the eyes, behind tubercles on the head, in the ventral pleats, or around the genitals.

In this photo, you can see how the whale lice have clustered together on this whale’s face.

In this photo that Nan took in the South Pacific, you can see how the whale lice have clustered together just in front of the pectoral fin

Just as sloughed off whale skin can be found in the water, barnacles and whale lice that were once attached to their skin are sometimes shaken off after a breach, too. The louse was placed in a sample bag for future analysis.

"Their skin is so sensitive - they must tickle," Nan says. The lice feed primarily on algae that settle on the whale's body, sometimes eating dead skin from the whale as well.

Scooping skin isn’t always easy – if the pieces are small, or if conditions on the water are poor, it can be easily missed. Scooping for whale skin is further complicated by the abundance of plastic pollution now present in our oceans.

Here you can see pieces of plastic pollution that the Sound of Science team mistook for whale skin while scooping. Trash is almost indistinguishable from the humpback skin the research team is hoping for, a poignant illustration of the health of our oceans.

When scooping in a whale footprint, it is possible that skin from multiple different individual whales may be collected, especially if many whales have breached or exhibited surface behaviours in a short space of time. The goal is to match the skin with the fluke ID, dorsal fin and the behaviour of the particular whale. It is like putting all the puzzle pieces together and is sometimes quite difficult.

The collected DNA is compared to logs of whale interactions and whale fluke ID images captured on a particular cruise, in order to paint a complete picture of one individual whale’s behavior.

A dedicated website is coming soon, but for now please visit the Whale Song Project Page or Nan’s Website

Atlas the CahowCam 1 Chick has fledged!

Sometime between 11pm on May 25th and sunrise on the 26th, “Atlas” the newly named CahowCam1 chick fledged.

The Nonsuch Expeditions and Cornell teams had been doing their best to track her movements by using the remote-controllable PTZ (point, tilt, zoom) SurfaceCam, as she wandered around the colony exercising and imprinting on her surroundings, however, around midnight she made her way to the far side of the colony and did not return, ultimately fledging out of view of the camera.

In past years, the Team has been fortunate enough to be able to track and film the star birds as they launch into their first flight from areas within clear view of the camera, whilst followers from around the world watched in real-time via the LiveStream. Hopefully, this will still be possible for this years’ CahowCam2 chick which is expected to fledge around June 10th, and either way the Team will be tracking the other chicks from the colony as they prepare to and ultimately fledge.

Those interested should tune in nightly, after dark to watch the Cam 3 LiveStream.

2022 Cahow Season Sees Record Number of Cahow Fledglings

Jeremy with “Atlas” the 2022 CahowCam 1 chick.

Cahow fledging season is beginning on Nonsuch Island, with a record number of birds for the Cahow Recovery Project.

“From only 18 breeding pairs, making up the entire population of the Cahow when the program began in the early 1960s, the Cahow population has now grown to a record number of 155 breeding pairs, up from 143 pairs in 2021.

In addition, we can now confirm that there are a record number of chicks this year – 77 – compared to the previous record of 73 chicks in 2019 ”

The chicks are fledging (take their first flight and heading out to sea) from now until mid June, having been fattened up by their parents since they hatched in February and March.

The critically endangered Bermuda Petrel, or Cahow (Pterodroma cahow), Bermuda’s National Bird, is a football-sized fuzzball (until it sheds its down prior to fledging), with a wingspan of 35-36 inches when ready to fly.

When cahows fledge from Nonsuch, it is suspected they will not touch solid ground again for 3-5 years, wandering over the open ocean in there North Atlantic, feeding on squid, small fish, and crustaceans, and sleeping on the wing.

“The oldest of this year's cohort of chicks have just begun their pre-fledging exercise period, coming out of their underground burrows at night to exercise, strengthen their flight muscles, and imprinting on the area surrounding their nest. In their first flight, they will head straight out to sea,” says Jeremy Madeiros, principal conservationist for the Cahow recovery project.

“This imprinting is instrumental in enabling them to eventually make their way back to the same location, several years from now,” Madeiros explains. Remote Nonsuch Island, and the neighboring islands and rocks total less than 22 acres on the southeast coast of Bermuda, and is the only place on Earth where the Cahow nests.

The 60-year-running Cahow Recovery Project controls and manages threats to the Cahow on the breeding islands, and has enabled the species to recover from near-extinction. The incredible seabird was thought to be extinct for 300+ years until it was rediscovered nesting in a few remote Castle Harbour islets in 1951, by a team that included a young David Wingate – who was later appointed Bermuda’s first Conservation Officer in order to facilitate their recovery on Nonsuch in the 1960s.

Cahows were wiped out on Nonsuch Island and all the larger Islands of Bermuda by the 1620s due to introduced mammal predators such as rats, cats, dogs, and hogs, and hunting by the early settlers.

Two separate translocation projects, carried out in 2004-2008 and 2013-2017, succeeded in re-establishing two new nesting colonies (A&B) in different locations on Nonsuch.

These colonies have been so successful that since 2009, when the first returning pair produced a chick on Nonsuch for the first time in 300 years, the Nonsuch colonies have increased to a total of 31 nesting pairs, producing a record number of 16 chicks in 2022

“Throughout the entire Colony, from only 18 breeding pairs, which made up the entire population of the Cahow when the program began in the early 1960s after their remarkable re-discovery in 1951, the Cahow population has now grown to a record number of 155 breeding pairs, up from 143 pairs in 2021. In addition, we can now confirm that there are a record number of chicks this year – 77 – compared to the previous record of 73 chicks in 2019,” Madeiros reports.

On March of 2022 Rouja logs into the latest generation of CahowCam, now buried underground on the side of burrow #831 – viewing the birds without ever having to remove the lid of their artificial burrow.

The Cahow Recovery Project has been able to garner huge amounts of data and insight into the behaviour of the birds on land, in a large part with the help of the CahowCam, an innovation of Nonsuch Expeditions Founder and conservation tech developer Jean-Pierre Rouja. The CahowCam broadcasts the activities of the endangered birds from within their underground nesting burrows.

It consists of a camera embedded into a PVC pipe above the nest for easy maintenance, surrounded by a ring of special LED bulbs, designed to light up the cahow’s activities, but not to be detected by their extremely light-sensitive eyes. The CahowCam recently celebrated its 10-year broadcasting anniversary. You can learn more about this conservation tech development, which is paving the way to study other difficult-to-observe target species, here.

The CahowCam has allowed locals, students, and scientists from around the world to watch the complete breeding cycle of one of the rarest seabirds on the planet – without ever disturbing them.

“As in past years, we will be tracking the Cahow chicks using our remotely controlled infrared surface Cam as they spend a few nights wandering around the colony exercising and imprinting on their surroundings prior to fledging, and if all goes well, we will actually witness them launch into their first flight,” says Rouja.

In addition to a record number of chicks, the 2022 breeding season will also see another first – the fitting of a global location sensor (GLS) tag on a juvenile fledgling bird. Up until this point, the Cahow Recovery project has only fitted a handful of GLS tags on adult birds, giving them insight into where the mature birds went between nesting periods – but no one knew what the birds did during the period after they left Nonsuch for the first time, and returned 3-5 years later to make a nest of their own. Fitting a fledgling with a small GLS tag will provide positional data on what might be termed the cahow’s ‘lost years’.

The GLS tag is seen on the left leg and the identification band on the right.

“This has never been carried out on fledglings before, and their movements during this vital developmental period are completely unknown,” says Madeiros. “This information will be vital in determining whether they are encountering threats at sea – for example, from industrial fishing activities, or areas on the Canadian continental shelf where oil and gas extraction and exploration are taking place.”

A total of 37 birds will be fitted with GLS tags, provided by research partner Letizia Campioni. The tags record daily positions of the birds for up to 32 months – around the time the tags stop recording, the birds are expected back at Nonsuch. The tags do not transmit data live, but rather archive it – so the Cahow Recovery Project will only be able to see the data after the Cahows return and the tag can be retrieved.

“It will be a huge reward after 3 years of waiting!” Rouja jokes.

The CahowCam 1 chick, recently named “Atlas” by Madeiros’ daughter, Elizabeth, was fitted with an identification band and a GLS tag on Wednesday 18th May. You can watch the full video, captured by Rouja, below.

“Atlas” is now preparing to fledge – possibly as early as this weekend! You can tune in to watch the chick’s activities here.

Bermuda Skink May Depend on Cahow To Thrive

For Endangered Species Day, the Nonsuch Expeditions are showcasing two of Bermuda’s Critically Endangered, IUCN Red Listed species that live together on Nonsuch Island.

Senior Terrestrial Conservation Officer Jeremy Madeiros, head of the Cahow Recovery Project, has observed something remarkable this year – as he records the highest number of chicks ever in the Cahow breeding colony on Nonsuch Island, the population of another critically endangered animal is increasing too: the endemic Bermuda skink.

“It seems that where Cahows nest, skinks tend to be doing better, too” Madeiros says. He believes it is likely that the Bermuda skink co-evolved with the Cahows and Audubon’s shearwaters that used to live in vast breeding colonies on Bermuda’s islands, and that the skink’s success may be tied to the Cahow’s.

Thanks to a groundbreaking 60+ year rewilding effort that has seen Nonsuch Island restored to pre-colonial Bermudian habitat, allowing Cahows and skinks to thrive without the threat of introduced predators, we can observe these two critically endangered species interacting once more.

“The skinks spend time in and around Cahow burrows – and the birds don’t seem to mind,” Nonsuch Expeditions Founder and CahowCam creator Jean-Pierre Rouja says, as has been documented in footage from the CahowCams, his special camera set ups that allows video from inside the underground nesting burrows to be broadcasted to the world without disturbing the birds.

In the video below from 2019 the skink arrives around the 1:47 mark (Stormy has not yet been seen this season).

Why do the skinks want to cozy up with the fluffy chicks? Likely to take advantage of the safe shelter of their underground burrows, and to forage for food. Skinks have a very variable diet, including fruit, insects, and carrion. They occupy a cleaning role in Cahow nests, eating insects like ants that bother the chicks. They will also eat spilled food and bird droppings, and when an egg fails or a chick dies, they will go in rapidly and scavenge it.

“They provide a valuable function for the Cahows, keeping nest burrows disease free. They're like little live-in housekeepers almost. They benefit from the shelter, and in turn they keep the nests nice and clean and healthy,” Madeiros says.

Living in a Cahow burrow probably gave skinks a better chance of survival when they first colonized Bermuda, likely by travelling over the ocean on floating debris, about 400,000-2 million years ago. Through re-establishing the Cahow, this ancient relationship has also been reconnected.

A conservation team in New Zealand had a similar story, says Madeiros. “In areas where they were increasing shearwater populations (a ground-nesting bird related to the cahow), tuataras also increased – a reptile endemic to the area that's kind of like a cross between a lizard and a dinosaur. The tuataras used the burrows for shelter, and the birds were not bothered by the lizards. Now we can see a similar thing going on with the skink in Bermuda. It seems more and more obvious that Cahows and skinks have had this semi-symbiotic relationship for thousands of years - perhaps millions.On the Bermuda mainland, skinks are now only found in small, fragmented populations in specific habitats. On Nonsuch, Madeiros says the skink populations located away from the Cahow colony have plateaued or even decreased, while those living close to the Cahows have skyrocketed.

“There were only 7 or 8 skinks living where the main Cahow colony is on Nonsuch Island in 2009. Now, 12 years later, I would estimate we have 50-60, possibly 70 living there,” Madeiros reports.

The next step will be for Madeiros to ground proof his empirical observations by conducting another skink survey, which will involve trapping the skinks and determining their population numbers.

"It’s a nice little symbiosis. The Cahow recovery plan has unintended beneficial side effects - we are even helping other species as well."

Meet the Easter Cahow chicks

This Easter there are a record number of 11 Cahow chicks in Nonsuch Island Translocation Colony “A” (and 5 in Colony “B”), including our two star CahowCam chicks, with our CahowCam 1 chick being over 400 grams and the heaviest in the Colony!

See the portraits, then watch the video tour below.

BUEI Talks: "A Symphony of Whales: The Song that Changed the World’

A BUEI Talks session titled ‘A Symphony of Whales: The Song that Changed the World’, presented by Nan Hauser, co-founder of the Bermuda Whale Song Project and President and Director of the Center for Cetacean Research and Conservation, will take place on April 6th. Reception with complimentary beverage at 6 pm, talk starts at 7pm.

“Nan, who first fell in love with whales in the waters of Bermuda, turned her passion into a profession garnering over 30 years of experience in the field of whale research. ‘The Whale Who Saved Me’, a now viral video, captured the harrowing moments when a humpback whale shielded her from an approaching tiger shark by pushing her to safety with his head and pectoral fin, has been viewed by more than 600M people worldwide.

“She’s recently returned to Bermuda to collaborate with Nonsuch Expeditions Founder, Jean-Pierre Rouja, to determine how the whale songs heard in Bermuda could potentially be used in the conservation of the species.

“Nan’s BUEI Talk presentation will focus on the ‘Sound of Science’ Bermuda Whale Song Project, a collaboration with Nonsuch Expeditions, Center for Cetacean Research and Conservation and Cornell University Bioacoustics Lab. The ‘Sound of Science’ is an acoustic study involving the ongoing analyses of humpback song and behavior from different parts of the world. Bermuda is set to play a significant role in this study with acoustic recorders being deployed in our waters to capture the sounds of humpback whales passing by our Island.

“The first recorded whale song, entitled ‘Solo Whale’, which was first discovered in Bermuda, will also be covered in her talk.”

Tickets for BUEI Talks with Nan Hauser are $25. Each ticket includes entry into BUEI’s Ocean Discovery Centre from 6pm-7pm and a complimentary beverage courtesy of Gosling Brothers.

April 1st CahowCam 1 and 2 health checks

Jeremy conducts health checks for our CahowCam1 & 2 chicks on April 1st and finds that the Cam1 chick is the heaviest in the Colony!

Watch the LiveStream here.

Going for a song: Researchers launch whale research project →

The Royal Gazette March 29th: Bermuda is to become a field station for a new study on the songs of humpback whales, it was announced yesterday.

The study, “Sound of Science”, will explore differences in song trends and phrases between North Atlantic whales and their South Pacific counterparts.

J-P Rouja, the team leader for Nonsuch Expeditions, said the conservation group had teamed with the Centre for Cetacean Research and Conservation based in the Cook Islands and the US, and Cornell University, in New York State.

Mr Rouja told The Royal Gazette: “The story of whale song starts in Bermuda, which is the first time whale song was recognised for what it was.

“Whale songs change from year to year. Locally it has been recorded sporadically over the past 30 or 40 years but not as a proper ongoing study.

“We’re basically starting a new series of recordings.”

Press Release - Bermuda Whale Song Project

“Sound of Science”

Bermuda Whale Song Project

The EVOLUTION OF WHALE SONG IN BERMUDA

RESEARCH PERMIT / PROTECTED SPECIES LICENSE NO. 2022031701

After several years of planning, in the spring of 2022, a new project collaboration between The Nonsuch Expeditions, The Centre for Cetacean Research & Conservation, and Cornell University has been launched. This timely project brings us back to the place where humpback whale song was first recorded.

Bermuda has a long history of scientific studies of whales, including their songs. Frank Watlington, a Bermudian, recorded humpback whale songs in the 1950s while working with the US Navy. The Bermuda recording “Solo Whale” was a vinyl record insert in National Geographic Magazine in 1979. Sharing the song was instrumental in the “Save the Whales” movement back then. Our initial project focus is to capture current recordings of Bermuda whalesong, compare them with historical recordings and examine the song trends and phrases between the North Atlantic and the South Pacific.

Bermuda, once again, will be the focal point.

If you would like to arrange a talk or presentation to learn more about the project and Nan’s three decades of wild whale experiences around the world, please contact: jp@nonsuchexpeditions.com or nan@whaleresearch.org or call phone # 333-5555

To learn more visit: http://www.nonsuchisland.com/whales

A record # of Cahow chicks are hatching this season

Here is a brief summary of the Cahow nesting season so far:

As of March 19th, 2022, all viable eggs have now hatched in the Cahow nesting islands; I have been visiting as many of the breeding colonies as possible to get an idea of the number of hatched chicks at each site, as compared to the total number of nesting pairs which have produced eggs this year.

Although the final tally is not yet complete, this is what we know at this point:

Nonsuch Island: 16 hatched chicks (previous Nonsuch record was 13 chicks in 2021), out of 31 active breeding pairs.

Green Island: 17 hatched chicks (previous record 13 chicks), out of 26 active breeding pairs.

Horn Rock: 28 hatched chicks out of 49 active breeding pairs

Inner Pear Rock: 8 hatched chicks confirmed so far from 14 out of 21 active breeding pairs checked to date.

Long Rock: 7 hatched chicks out of 13 active breeding pairs.

Southampton Island: Not checked yet.

As of this date, it looks like there are at least 75-76 confirmed chicks, compared to the record number of 73 successfully fledged chicks in 2019; there were 69 in 2020, and 71 in 2021.

Although the numbers will be adjusted as the deeper natural nests can be confirmed, and not all chicks may make it to fledging, so far it looks like we have a very good chance of setting a new record number of fledged chicks for the 2022 season.

Jeremy Madeiros | Principle Scientist - Terrestrial Conservation | Dept. of Environment and Natural Resources | BERMUDA

Meet the CahowCam 2 Chick

On March 11th at around 11 pm, our CahowCam 2 chick finally hatched. It was an abnormally long hatching process as Jeremy had first seen signs of dimpling 5 days prior, but in the end, it went smoothly. Watch a video of its first health when it was 3 days old below. Watch the LiveStream here.

Audubon Magazine: How Webcams Are Helping Scientists Save One of the World’s Rarest Seabirds

Article By: Aaron Tremper Editorial Intern, Audubon Magazine

For the past decade, the CahowCam Project has entertained viewers while revealing new insights into the lives of the endangered Bermuda Petrel.

JP Rouja makes adjustments to CahowCam 1 | Photo Chris Burville

Article Excerpt: Just after midnight in March, 2017, an intruder enters a seaside burrow on Bermuda’s Nonsuch Island. He’s a young male Bermuda Petrel, or Cahow, a 15-inch-long seabird wearing slick gray-and-white feathers. He is also one of only 350 or so individuals left of his species in the world. As the bird waddles into the basketball-size nesting cavity, he’s excitedly greeted by a fluffy mass of down—a cheeping, five-day-old Cahow Chick waiting for its parents to return with a meal.

But the young male is not the chick’s parent; he is an invader looking to take over the nest. He suddenly grabs the chick’s neck with his hooked bill and starts biting. The next 18 minutes are tense, as the male alternates between scoping out the nest and assaulting the chick. Unsatisfied, he finally exits the chamber, leaving behind a shaken but otherwise intact nestling.

This encounter—caught on camera and livestreamed to thousands of online viewers—was the first time Cahow conservationists had ever observed such a behavior. At that point, researchers were well aware of the dangers that invasive rats, land crabs, and competing tropicbirds pose to young petrels. But this video footage documented an unknown threat to the endangered seabird: other Cahows.

The discovery is one of several made by The CahowCam Project, a set of livestreaming webcams currently in its 10th season of monitoring Cahow nesting burrows of Nonsuch Island, a 14-acre wildlife sanctuary in Bermuda. The project consists of three cameras: two tucked away in nesting cavities, and one stationed outside of the two burrows. Jean-Pierre Rouja, a photographer and environmentalist who founded the project in 2013, runs and maintains the livestreams. Last year, they collectively saw roughly 450,000 views from people around the world… Read the Full Article: https://www.audubon.org/news/how-webcams-are-helping-scientists-save-one-worlds-rarest-seabirds