When whales perform surface behaviours - like slapping their tail or pectoral fins, or jumping out of the water for a breach, lots of skin sloughs off their bodies into the water. In fact, one of the many theories for why whales breach is to remove parasites and exfoliate their skin.

“I never knew whales left so much material in the water before Nan explained it,” Jean-Pierre Rouja, project co-founder says. “ Alongside the whale songs the we are recording and archiving, the DNA that will be extracted from their skin is crucial for giving us more information on the whales that we identify in the Sound of Science project.” (Being conducted under PROTECTED SPECIES LICENSE NO. 2022031701)

These little flakes are sloughed-off skin from a humpback whale!

Sometimes the pieces of skin are so large, they can be seen floating in the water in a whale footprint – an area of smooth, glassy surface water left as a consequence of whale movement.

Nan Hauser, project co-founder says: “We can tell many things from whale skin … for instance the species, genetic clade, what they have been eating, their health, and much more. It is more common for us to find sloughed skin in the warmer waters than the colder waters. It is also more common to find sloughed skin from a female that has just given birth. We try hard to collect a piece of skin from every whale encountered but it is sometimes difficult.”

Nan has also collected whale placenta, bloodclots, cookie cutter shark bites of whale flesh, calf spew, whale poo, and sperm in the water. Do not make the mistake of going to Nan’s freezer to look for a midnight snack!

As soon as a whale breaches, the Sound of Science team enters the footprint it has left behind in order to scoop skin from the water with a net.

The Sound of Science project team can identify individual whales by photographing the ventral side of their tail flukes or the right and left side of their dorsal fins. Each whale fluke has different markings that can help with differentiating it from others in a group. The DNA analyses from the skin samples are matched to our ID photos, and to records of the whale’s observed behaviour.

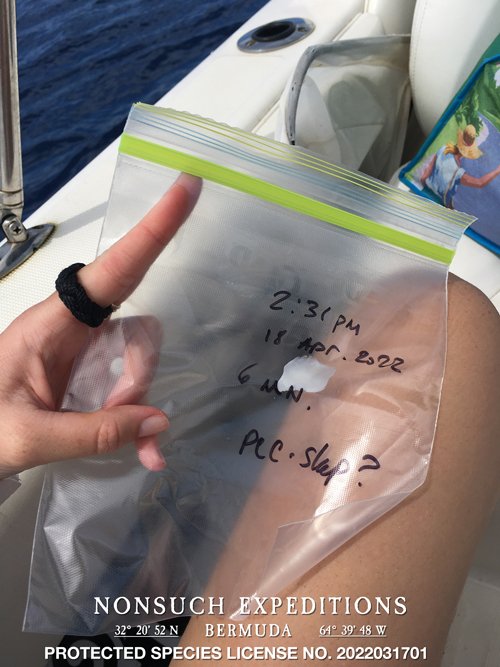

Here, you can see research assistant Choy Aming using tweezers to carefully remove collected skin from the sampling net. The pieces are quite large as they were collected from a breaching whale. Choy avoids touching the skin with his fingers, as it can contaminate the sample. Tweezers are sterilized with ethanol between net scoops. The skin is placed into a sample bag, which is labelled with the species – always Megaptera novaeangliae for this project – number of whales present, latitude and longitude of where the sample was scooped from, the time and date it was collected (which together with voice logs, help connect it to photographed fluke ID’s) and if there was a behaviour associated with it.

On one of the Sound of Science research days, research assistant Eric Manfra scooped something bright white from the water,which is probably a piece of skin from a humpback’s long pectoral fin since it as slapping its fin on the surface of the water.

On the same cruise, research assistant Fae Sapsford scooped a whale louse that was floating in the water after a breach.

Whale lice are little parasites that usually live on the skin of whales, settling in any crevice on the whale’s body that will protect them from water currents - like near the eyes, behind tubercles on the head, in the ventral pleats, or around the genitals.

In this photo, you can see how the whale lice have clustered together on this whale’s face.

In this photo that Nan took in the South Pacific, you can see how the whale lice have clustered together just in front of the pectoral fin

Just as sloughed off whale skin can be found in the water, barnacles and whale lice that were once attached to their skin are sometimes shaken off after a breach, too. The louse was placed in a sample bag for future analysis.

"Their skin is so sensitive - they must tickle," Nan says. The lice feed primarily on algae that settle on the whale's body, sometimes eating dead skin from the whale as well.

Scooping skin isn’t always easy – if the pieces are small, or if conditions on the water are poor, it can be easily missed. Scooping for whale skin is further complicated by the abundance of plastic pollution now present in our oceans.

Here you can see pieces of plastic pollution that the Sound of Science team mistook for whale skin while scooping. Trash is almost indistinguishable from the humpback skin the research team is hoping for, a poignant illustration of the health of our oceans.

When scooping in a whale footprint, it is possible that skin from multiple different individual whales may be collected, especially if many whales have breached or exhibited surface behaviours in a short space of time. The goal is to match the skin with the fluke ID, dorsal fin and the behaviour of the particular whale. It is like putting all the puzzle pieces together and is sometimes quite difficult.

The collected DNA is compared to logs of whale interactions and whale fluke ID images captured on a particular cruise, in order to paint a complete picture of one individual whale’s behavior.

A dedicated website is coming soon, but for now please visit the Whale Song Project Page or Nan’s Website