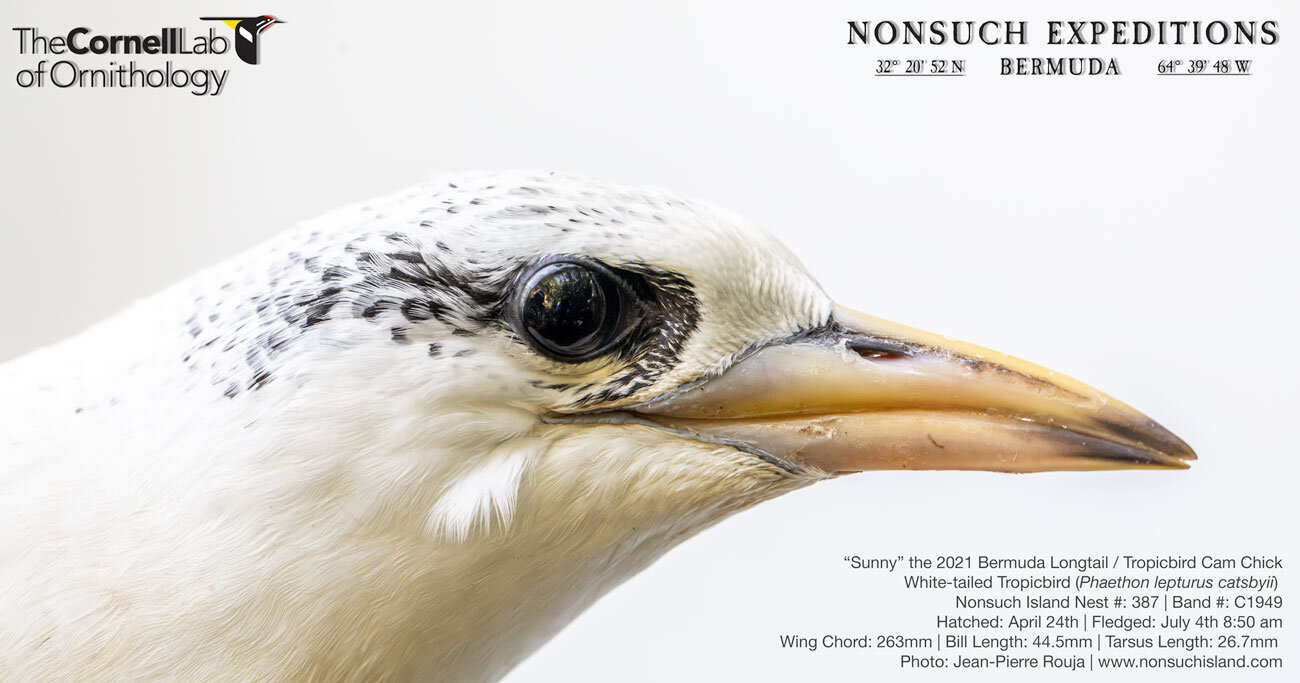

At 8.50am on the 4th July 2021, The “Bermuda Longtail” White-tailed Tropicbird chick (Phaethon lepturus catsbyii) that has been followed since it hatched on the 24th April at the Artificial nest-site # 387 (which is fitted with a Nonsuch Expeditions / Cornell Lab of Ornithology live-stream video camera) at the Nonsuch Island Nature Reserve on Bermuda, fledged successfully out to sea at 71 days of age.

“Events at this nest for the 2021 nesting season have been fairly dramatic, to say the least; after laying one of the earliest recorded eggs for this species, around the 7the March, the pair of Tropicbirds that have made this nest their home for the last 6 years hatched their egg on the 24th April. This made it the first Tropicbird chick to hatch in 2021 out of the hundreds of nests monitored every year on the Castle Harbour Islands Nature Reserve on Bermuda, home to the largest concentration of breeding White-tailed Tropicbirds in the North Atlantic.”

“Only a couple of weeks later, around the 5th of May, there was further drama as the adult female bird stopped visiting this nest. This was almost certainly due to the death of the bird at sea, perhaps due to predation by a large fish or Tiger Shark. Normally, the loss of one of the adults means that the remaining adult will not be able to adequately feed the chick, which will slowly lose weight and be unable to develop and fledge successfully unless we intervene and take the chick into care to hand-feed it.

The Male bird from this pair, however, is an exceptionally healthy, vigorous bird that has experience in raising several successfully fledging chicks, and for the next two months, was able to carry out one to three feeding visits almost every day! This is when the value of regular weekly growth checks of the chicks was highlighted since I was able to confirm that not only was the chick being fed enough Squid and Flying Fish to grow normally with above-average body weights, but the adult male bird was also able to catch enough food to maintain its own body condition at a normal weight. This is very rare for a single adult to be able to pull this off and to put this feat in context, the male did a better job of feeding and taking care of the chick than most adult pairs, working together, are able to achieve.

Even though our “Tropicbird Cam” chick has now departed and fledged out to sea, the Tropicbird Breeding Success Survey, which has been carried out annually for the last 16 years (since 2006) is only at the midway point. Every year for this survey, I monitor over 300 Tropicbird nest sites at ten study locations around the eastern half of Bermuda. This is done because Bermuda supports the largest breeding population of the subtropical seabird species in the Atlantic Ocean (over 3500 breeding pairs), making this an internationally significant population for the species. During this survey, the breeding success rate and number of successfully fledged chicks are recorded. And all adult birds and chicks that can be safely reached are fitted with corrosion-resistant identification leg bands, to ensure individual birds can be positively identified over their entire lifespan. In addition, a subset of chicks are weighed and measured weekly as a study of chick growth rates, to gauge relative annual ocean productivity around Bermuda.

So far, as of July 4th, I have been able to visit about 250 of the 321 study nests. Although I do not band the chicks until they are at least half-grown, it has been possible to band 76 chicks and 14 adult Tropicbirds, and will be hopefully continuing this work until the last chicks fledge by late September to early November. Bermuda was hit by 2 hurricanes in the latter part of last year’s study period, and a good deal of work has had to be carried out this season to repair damaged nests so that the birds (both Cahows and Tropicbirds) could use them. Hopefully, hurricanes will give Bermuda a wide berth in 2021!”

Jeremy Madeiros | Principle Scientist – Terrestrial Conservation, Dept. of Environment and Natural Resources, Bermuda Government