Students around the World were once again watching LIVE when our CahowCam chick hatched as part of our global educational outreach.

Now in our 6th year Live Broadcasting this annual event, a large portion of the hundreds of thousands of viewers and millions of minutes of video that is being watched is from students in various educational settings around the world.

This will be greatly enhanced next season with the rollout of the STEAM US standards based K-12 Curriculum that we are developing with Cornell that will then be translated into the Cambridge curriculum for global reach. Educators should sign up to our Newsletter for further updates.

Below is just one example of a classroom in Bermuda that has been following the CahowCam:

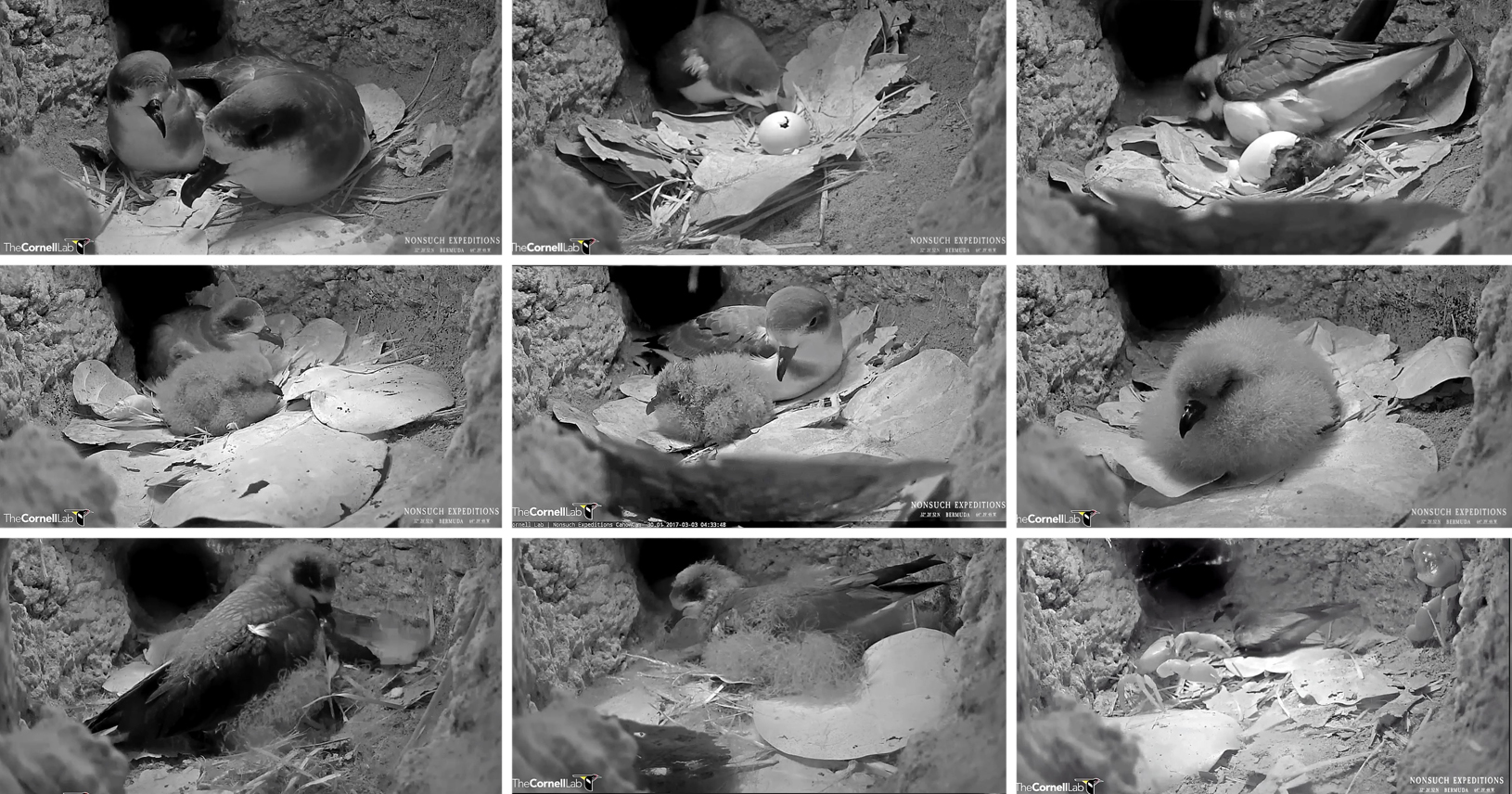

"The West Pembroke School Primary 2 students and their teachers cheered with delight on Friday, March 2, 2018, as we watched the cahow chick finally emerge from its egg.

The children have been watching daily ever since January 12th, when the female flew in hurriedly and layed her egg.

For 7 weeks, we kept our vigil, and we were very excited when Mr. Madeiros announced on Feb. 28th, that there were dimples on the egg, and it would hatch soon. How amazing that the hatching occurred right before our eyes! We were so thrilled, that the teachers took the laptop to the Assembly Hall and the entire school had the pleasure of seeing the chick’s first few minutes of life!

Thank you, Nonsuch Expeditions for making this incredible learning experience available, not only to the children of Bermuda, but to the entire world!"

Rhelda Wilkinson & Makeila Ming, P2 Teachers at West Pembroke Primary, Bermuda